The evolution of an economy is generally a slow process; in stark contrast, the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) took just weeks to flip our socio-economic systems upside down. In the United States, a technologically advanced nation, despite long efforts to modernize education and workforce pipelines, there was not enough urgency to drive critical changes to turn around the slide in American competitiveness, and we were not prepared to meet the resulting immediate and non-evolutionary challenges in our labor market. With the pandemic having put millions out of work, causing businesses to close (some permanently), and fostering distrust and fear worldwide, it now imperative to drive impactful change strategies for our new reality, and to create a future of work that will drive the next century of growth.

The Problem

There has been a growing realization of two major issues that have not been addressed adequately in the U.S., causing a loss in ability to compete at the highest levels globally. One is a shortage of sufficiently skilled labor in the industry workforce, and second is the inability of our 100-year old education system to meet the demands of rapidly changing workforce. In other words, the skilled labor pipeline is broken. Workforce changes are due to increased automation, a rising “gig economy” as workers have been displaced from traditional corporate and industrial jobs, and a lack of effective technology tools to enable a growing segment of the workforce to work remotely. Emergence of the COVID crisis of 2020 has made these problems exponentially worse. There was already a rising call to transform education to deploy human capital more effectively and to take on a digital transformation to meet the changing needs of the U.S. economy. The systemic issues in education and technology already existed, COVID simply laid them bare.

Prior to COVID, the US, with 3% unemployment, did not have enough skilled workers to fulfill the needs of the growing economy. However, there were still pockets of unemployment in the 12-14% range, typically in socially disadvantaged areas. Now nearly one year into the crisis, COVID has displaced more than 2.4 million American workers for more than 27 weeks (Federal Reserve of St. Louis, 2020), and there is no guarantee that their former jobs will return in a COVID or post-COVID world.

One study shows that 43% of small businesses have temporarily closed across a sample of 5,800 (Bartik, et al., 2020). The same study notes the fragility of U.S. economics and reliance on small companies re-opening, saying, “The fate of the 48% of American workers who work in small businesses is closely tied to the resilience of the small business ecosystem and to the massive economic disruption caused by the pandemic.” Yet small businesses often lack the technological structure and systems to work remotely or re-skill their employees, which could exacerbate the unemployment crisis and force many small businesses to close permanently.

(U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020)

Those without access to broadband networks have fewer choices and skills to reposition themselves in our new economy. PEW’s research on the digital divide highlighted issues even before the pandemic:

Without reliable high-speed internet service, communities cite a growing gap between the resources and opportunities available to their residents and those in communities with a robust network. Recognizing the importance of broadband and responding to such frustrations, states are seeking to close this gap. Most have established programs to expand broadband to communities that lack it or are underserved (PEW Charitable Trusts, 2020).

The digital divide creates an uneven and underskilled workforce, hindering the expansion and development of businesses to rural areas and complicating the process of re-skilling those with the raw ability to work, but either lacking the technology or access to technology (Winslow, J., 2019).

The Opportunity

There are few things which happen that can drive change more effectively than a crisis. Even with everything that we believe about the strength of our economy and resilience of society, a crisis of the severity of COVID in 2020 exposes longstanding problems and injects enough urgency to necessitate the creation of a “new normal.” This level of change can be thought of as a pattern interrupt, evidenced by the closure or severe restriction of businesses and a nearly global transition to remote working and reliance on technology solutions for everyday activities. It also exposed the severity and widespread nature of the digital divide, the need for better technology tools, a lack of remote learning skills, and the inadequate state of education systems to reskill the workforce. Change is no longer a choice, with forced change playing out in education and the needs for re-skilling the workforce, especially related to technological advances.

Solutions Approach

New approaches are necessary to reimagine and strengthen the workforce in the “new normal.” There is an immediate need to understand dislocated workers’ talents and abilities. It is essential to comprehend workers’ current skills to properly train and re-train them to satisfy new workforce practices and requirements. Reskilling will facilitate the re-opening of small businesses and introduce dislocated workers to new opportunities within other firms which have sustained through the pandemic. It also includes companies imagining (and reimagining in a short timeframe) the skills workers need to thrive in the new economic structure and gaining the ability to work remotely.

In understanding the lived reality our workforce faces, as leaders we can help re-position individuals through understanding their unique skills and abilities and providing affordable training. Tackling some of our systemic issues, reaching students at a young age and workers at their current level of technical knowledge and learning capacity is a vital part of ensuring an agile workforce. It is clear that in a COVID world, those who cannot learn, unlearn, and re-learn fall behind as our skill needs and technology advance at an exponential rate. Already partially true in a pre-COVID world, reskilling and multi-generational training is now essential for workers to move between or even to stay within a work sector(s). Such activity includes establishing soft skills such as agile abilities from a young age, throughout all levels of education and into the current workforce.

Pre-pandemic, both the digital divide and the disastrous consequences of prolonged poverty have purposed leading organizations like Microsoft to create data-driven solutions. Examples include Microsoft’s Digital Literacy classes and tools, free learning content, discounted exams, tools to help job seekers get hired, and incentives for employers to hire and upskill (2020). One particular initiative—DigiGirlz—provides access to middle and high school females for exposure to careers in technology (Microsoft DigiGirlz, 2020).

Much like Microsoft, the team at Spark Growth applies academic rigor to understanding & addressing social problems by focusing on data and metrics to guide improvements to the issues facing communities. We bring real tools to students to drive change in education, and leverage technology as an enabler to solve widespread social problems such as the digital divide. Developing multi-generational, community-driven projects like DaVinci’s Faire creates a renaissance in the way citizens view STEM education, entrepreneurship, and helps instill a wonder of discovery in our young people (https://davincisfaire.com).

The manufacturing sector offers a particularly rich case study. According to a Deloitte Skills Gap report (2018), in 10 years, 2.1M new jobs will be needed in the U.S. for advanced manufacturing, but at the same time, 3.8M workers are 55+ and retiring. With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, manufacturers must automate for efficiencies, retrofit lines for safety, and account for new deployments. The manufacturing industry is over US $2.33 trillion and rising. While industry needs are changing, and multifaceted skills are more in demand in the workforce, there are also unique local and regional needs to be satisfied. Yet, research shows one-third of workers are currently without the technical skills to adjust. Likewise, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and prioritized the need for skilled talent in manufacturing, and the need for reskilling of the workforce due to increased automation is becoming a reality. This demands an education system to keep pace with these changes (BEA).

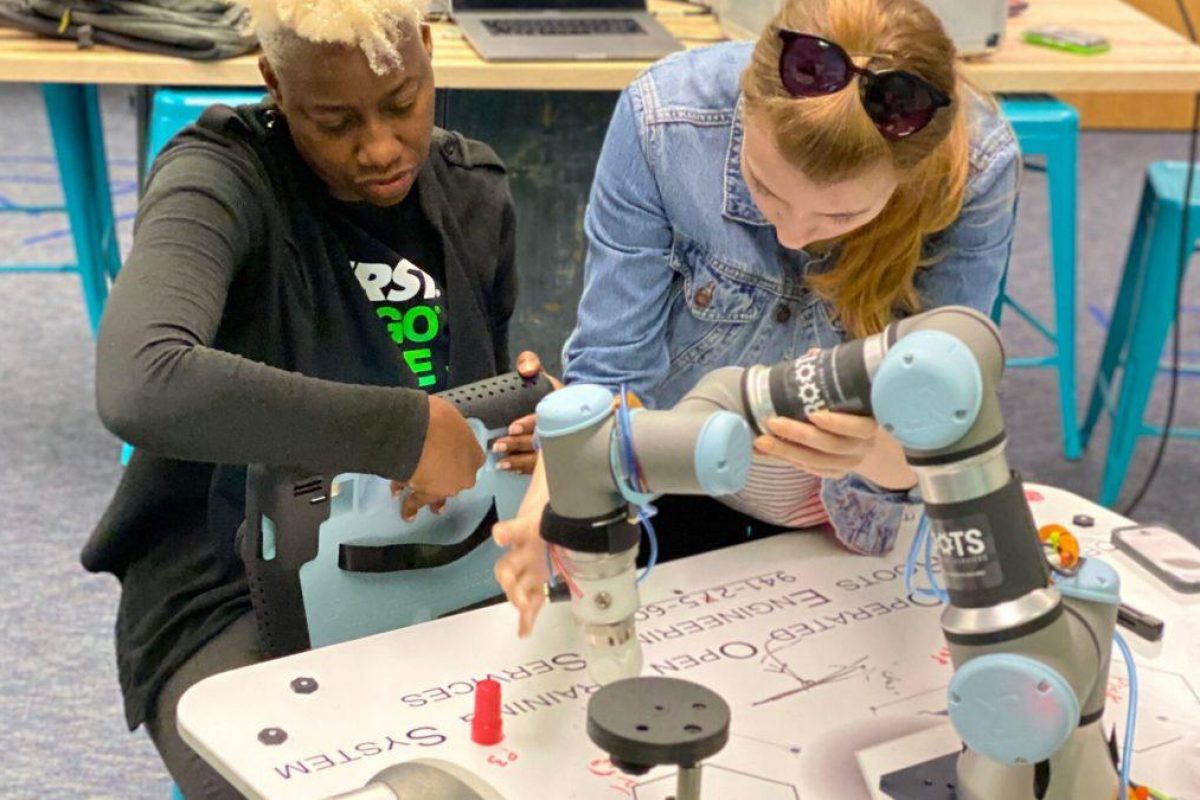

ROOTS Education is one of Spark Growth’s partner initiatives and focuses on skilling and reskilling in the manufacturing field, where there is a rapidly growing talent gap. We have established that the education market today does not meet industry needs. Using robotics as an example, tech education is not adaptable, agile, or creative, and most robotic systems sold into schools do not come with curricula. ROOTS Education fills this gap with a flexible and adaptable robotics training system. Technical curriculum and simulation capabilities keep students enrolled, engaged, and learning. ROOTS Education is age- and skills-appropriate for schools at the middle and high, Votech, and community college levels. It allows students to work remotely by providing robot simulators, which also increases the capacity and competitiveness of the learning systems. Beyond schools, ROOTS Education provides a similar level of engagement in workforce development and corporate/industrial re-skilling programs. Creating stackable certifications provides reimbursement to school classrooms for students’ certifications. Going beyond the classroom, certifications for incumbent workers provides a stepping-stone to higher-skilled jobs and commensurate pay levels.

Specific advocacy strategies developed with community partners (particularly new partners who work with clients directly on social issues) must include how to build capacity to engage dislocated workers effectively. Doing so requires a transformation of current spaces and available infrastructure to expand opportunities for adults and students entering the workforce with this new tech environment. Innovation cities, such as Aurora, Illinois, meet this challenge through dedicated resources such as the four pillars of Aurora’s 605 Innovation District: Safer, Connected, Better Run, and a more Prosperous City (Smart Aurora, 2020).

Looking holistically at systems and using empirical data in an agile and iterative fashion allows us to address complex social issues such as income, wage, and employment gaps with a focus on vital structural problems including student debt, racial profiling in employment, the absence of diversity in cutting-edge technology and advanced manufacturing, and wage discrimination, including asset-limited, income-constrained, and employed workers (United for ALICE, 2020).

Conclusion

The issues outlined in this paper address the real goals behind improvement of the education system and workforce pipelines: enabling economic development, because you cannot have economic development without an educated workforce. Harnessing the power of technology to deploy new education models and dedicating resources to deploying human capital more effectively. Enabling co-creation between education, industry and innovation leaders, and understanding the lived realities of all parts of society. Investing in programs for non-traditional students in our local universities and supporting underserved communities across the nation.

New technological tools and learning resources must be established to make skilling and re-skilling practices more responsive to the population’s educational levels, cultural diversity, and economic capacities. Aligning educational platforms with workers who have financial and time constraints due to parenting, work-school balance, and strain caused by COVID-19 is important. Informed by community-driven research, programs such as ROOTS Education are highly effective vehicles of change.

Certification programs and hands-on technical experience and have the power to re-develop our workforce quickly and effectively. They have a lower tuition cost than degree programs with less student debt due to shorter timeframes and fewer course materials purchased. Re-skilling programs also have a high return in creating jobs with mid- and high-range salaries. Targeted programs with an education-to-employment timeline that focuses first on students’ unique capabilities can address the time poverty many dislocated workers experience, such as single parents with multiple jobs.

Together we must focus on investing in workers and providing a comprehensive understanding of the competencies that are necessary in the workforce, including soft skills like problem-solving, effective communications, showing up on time, and learning patience, in addition to their technical skills. We are striving to empower workers to have more educational choices to position themselves to acquire more durable and flexible careers, matching the needs of employers. This “new reality” highlights barriers that have existed long before COVID that must be addressed after the coronavirus brought these challenges to light.

WORKS CITED

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17656-17666. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006991117

City of Aurora. (2020). Official Launch of Aurora’s 605 Innovation District. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://605innovationdistrict.com/

Federal Reserve of St. Louis. (2020, October 06). Layoffs and Discharges: Total Nonfarm. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTULDL/

Global Diversity and Inclusion, Microsoft. (2020). DigiGirlz at Microsoft. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/diversity/programs/digigirlz/default.aspx

Microsoft (2020). Accelerating Our Commitment to Skilling. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from aka.ms/skills

Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2014). Scarcity: Why having too little means so much. New York, NY: Picador, Henry Holt and Company.

The Economist. (2005, March 10). Technology and development: The real digital divide. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2020, March 20). How States Are Expanding Broadband Access. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/02/how-states-are-expanding-broadband-access

United for ALICE, United Way. (2020). MEET ALICE. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.unitedforalice.org/

Winslow, J. (2019, July 26). America’s Digital Divide. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trust/archive/summer-2019/americas-digital-divide

Attribution

Authored by: Stan Schultes and Sara Hand

Researched by: Cassandra Decker

Spark Growth, LLC

https://sparkgrowth.net, phone: +1 941 877 1599